Cycle Log 40

Multi-Modal Inertial Estimation and Reflex-Level Control for Dynamic Humanoid Manipulation

I. Introduction: Why Robots Still Can’t Cook

Despite major advances in humanoid robotics, modern robots remain fundamentally incapable of performing one of the most revealing and ordinary human tasks: cooking.

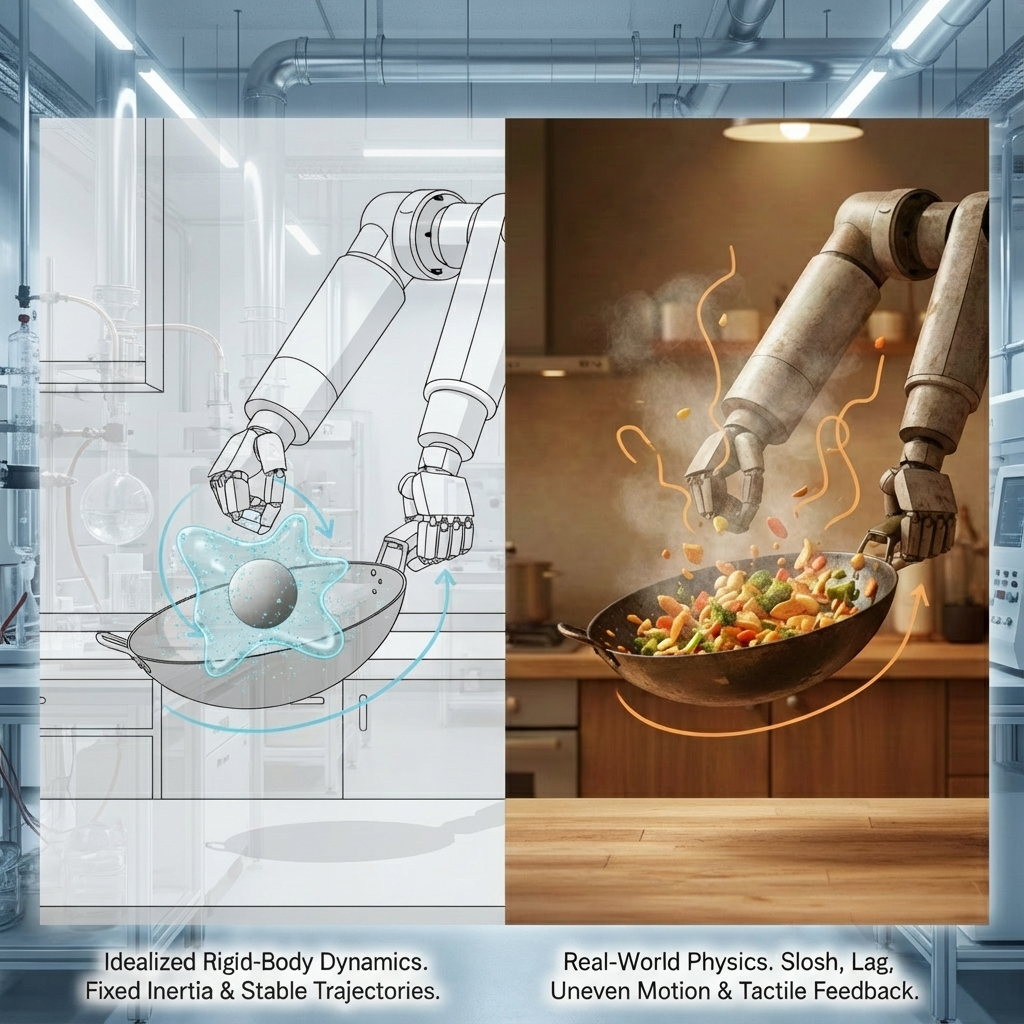

Figure 1. Failure of static manipulation assumptions in dynamic cooking tasks.

This limitation is not cosmetic. Cooking exposes a deep and structural failure in current robotic systems, namely their inability to adapt in real time to objects whose physical properties are unknown, non-uniform, and continuously changing.

Food does not behave like a rigid object. It pours, sloshes, sticks, separates, recombines, and shifts its mass distribution during motion. A wok filled with vegetables, oil, and protein presents a time-varying inertial profile that cannot be meaningfully specified in advance. Yet most robotic manipulation pipelines assume exactly that: known mass, known center of mass, and static contact dynamics.

Figure 2. Idealized rigid-body simulation versus real-world dynamic manipulation.

As a result, robots either over-approximate force and fling contents uncontrollably, or under-approximate force and fail to move the load at all. This is not a failure of strength or dexterity. It is a failure of perception and adaptation.

The central claim of this paper is therefore simple:

Cooking-capable manipulation does not require perfect world simulation. It requires real-time measurement of how a held object responds to action.

Humans do not simulate soup. They feel it.

II. The Core Bottleneck: Static Assumptions in a Dynamic World

Current humanoid systems fail at cooking for several interrelated reasons:

They assume object mass and inertia are known or static.

They rely heavily on vision-dominant pipelines with high latency.

They lack tactile awareness of grasp state and micro-slip.

They use fixed control gains inappropriate for time-varying loads.

They attempt to solve manipulation through precomputed simulation rather than online measurement.

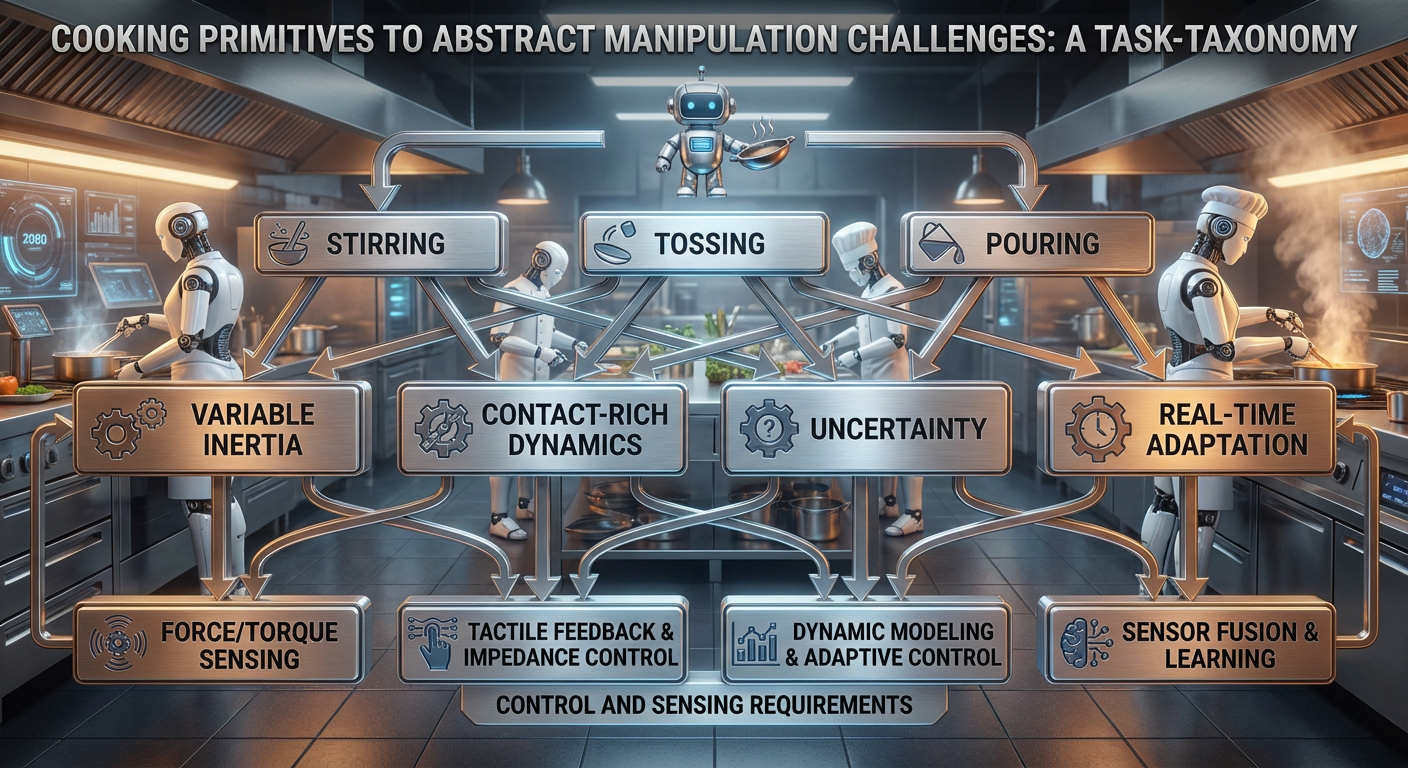

These assumptions collapse immediately in contact-rich, non-uniform domains. A robot stirring a wok must continuously adapt as ingredients redistribute, oil coats surfaces, and inertia changes mid-motion. Without an online estimate of effective inertial state, control policies become brittle and unsafe.

What is missing is not more compute or better planning, but a way for the robot to continuously infer what it is actually holding.

III. Human Motor Control as a Guiding Analogy

Humans are often imagined as reacting instantly to tactile input, but this is a misconception. Skilled manipulation does not occur through continuous millisecond-level reaction. Instead, humans rely on learned motor primitives executed largely feedforward, with sensory feedback used to refine and modulate motion.

Figure 3. Human motor control as feedforward execution with sensory modulation.

Empirically:

Spinal reflexes operate at approximately 20–40 ms.

Cortical tactile integration occurs around 40–60 ms.

Meaningful corrective motor adjustments occur around 80–150 ms.

Visual reaction times typically exceed 150 ms.

Humans are therefore not fast reactors. They are adaptive executors.

This observation directly informs the timing assumptions of the robotic system proposed in this work.

IV. Robotic Reaction Time, Sensor Latency, and Practical Limits

Unlike humans, robots can process multiple sensing and control loops concurrently.

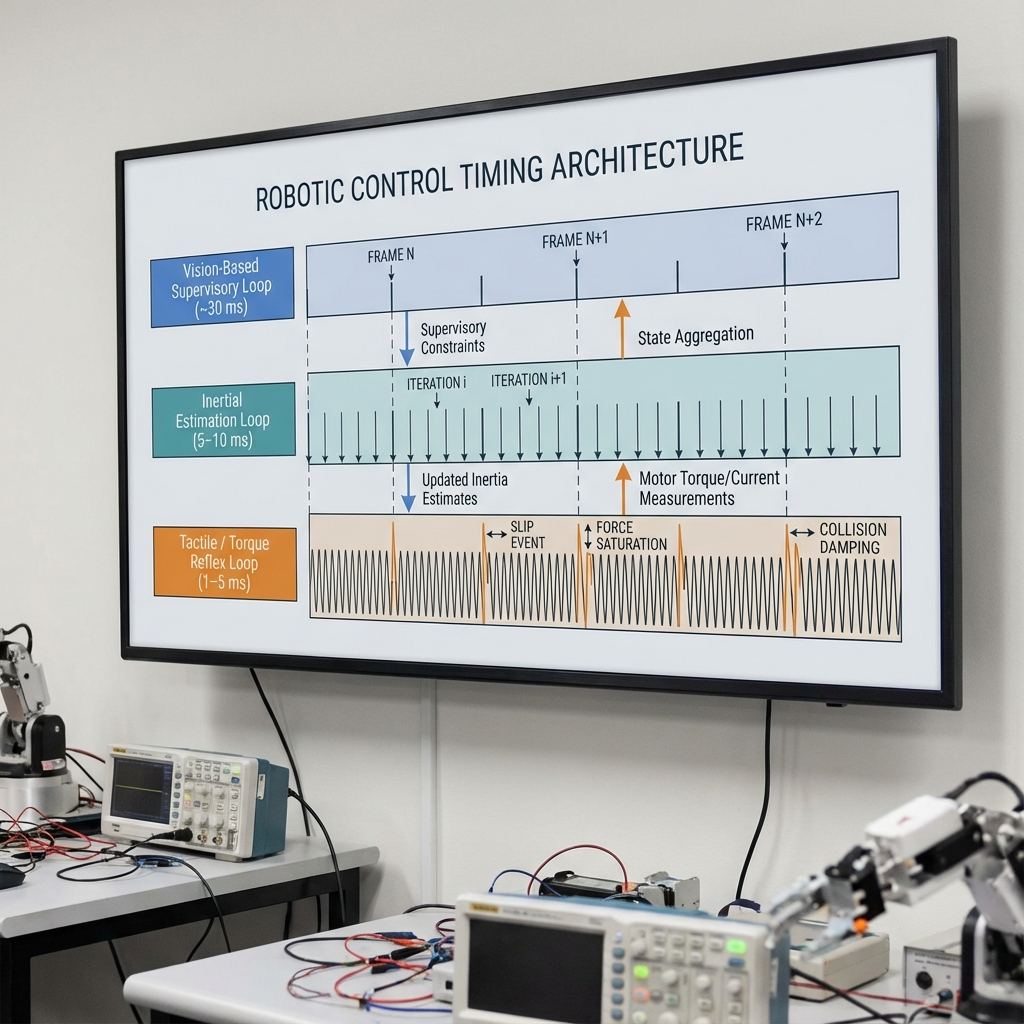

Figure 4. Multi-rate robotic sensing and control timing architecture.

However, the effective reaction time of a manipulation system is constrained by its slowest supervisory signal, which in practical systems is vision.

A frame-synchronous perception and estimation loop operating at approximately 30 milliseconds is therefore a realistic and conservative design choice. Importantly, this update rate is already:

5–8× faster than typical human visual reaction time

Faster than human cortical motor correction

Well matched to the physical timescales of cooking dynamics

Lower-latency signals such as tactile sensing, joint encoders, and motor feedback operate at much higher bandwidth and allow sub-frame reflexive responses within this 30 ms window. These include rapid impedance adjustment, torque clamping, and grasp stabilization.

Thus, while vision sets the cadence for global state updates, grasp stability and inertial adaptation need not be constrained by camera frame rate. This mirrors human motor control, where reflexive stabilization occurs faster than conscious perception.

The ~30 ms regime is therefore not a limitation or an early-phase compromise.

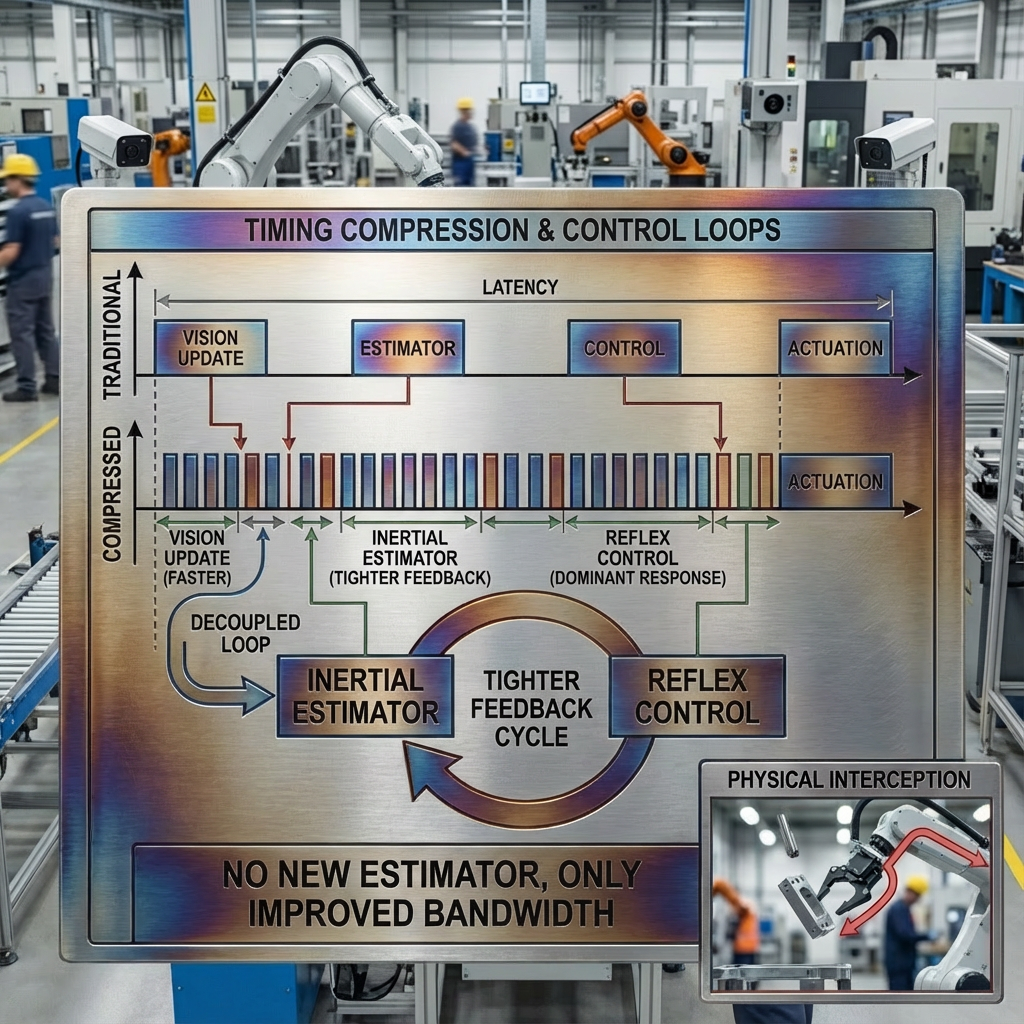

Figure 5. Latency compression through decoupled control loops.

It is a baseline capability, sufficient for household manipulation and already superhuman in responsiveness.

V. System Philosophy: Measurement-Grounded, Locally Densified World Modeling

The proposed system does not eliminate internal world modeling, nor does it operate as a purely reactive controller. Instead, it abandons the pursuit of globally exhaustive, high-fidelity environmental simulation in favor of a hierarchical world model whose precision is dynamically concentrated around the robot’s current task and physical interactions.

At all times, the robot maintains a coarse, stable background representation of its environment. This global model encodes spatial layout, object identity, task context, and navigational affordances. It is sufficient for planning, locomotion, sequencing actions, and understanding that “there is a kitchen,” “there is a wok,” and “this object is intended for cooking.”

However, the system does not attempt to maintain a perfectly simulated physical state for all objects simultaneously.

Figure 6. Locally densified physical modeling within a coarse global world model.

Doing so is computationally expensive, brittle, and ultimately inaccurate in contact-rich domains. Instead, physical model fidelity is allocated where and when it matters.

When the robot initiates interaction with an object, particularly during grasp and manipulation, the internal representation of that object transitions from a symbolic or approximate prior into a locally densified, measurement-driven physical model. At this point, high-bandwidth tactile, proprioceptive, and actuation feedback begin to shape the robot’s understanding of the object’s true inertial state.

In this sense, the robot’s internal “world” is dynamic and grounded. The majority of computational resources are focused on what the robot is currently touching and moving, while the remainder of the environment remains represented at a lower, task-appropriate resolution.

A wok, for example, is initially treated as an object with broad prior expectations: it may contain a variable load, it may exhibit sloshing behavior, and its inertia is uncertain. Only once the robot lifts and moves the wok does the system begin to infer its effective mass distribution, center-of-mass shifts, and disturbance dynamics. These properties are not assumed in advance; they are measured into existence through interaction.

This leads to a governing principle of the system:

The robot does not attempt to simulate the entire world accurately at all times. It simulates with precision only what it is currently acting upon, and only after action begins.

VI. Multi-Modal Sensing Stack and End-Effector Generality

A. Tactile Sensing

The system employs piezoresistive tactile sub-meshes embedded beneath a durable elastomer skin. These may be placed on dexterous fingers, fingertips, palm surfaces, or flat gripping pads.

Absolute force accuracy is unnecessary. The tactile layer is designed to detect differential change, providing:

Contact centroid drift

Pressure redistribution

Micro-slip onset

Grasp stability signals

These signals gate inertial estimation and prevent slip from being misinterpreted as inertia change.

Figure 11. Tactile grasp-state inference via differential pressure analysis.

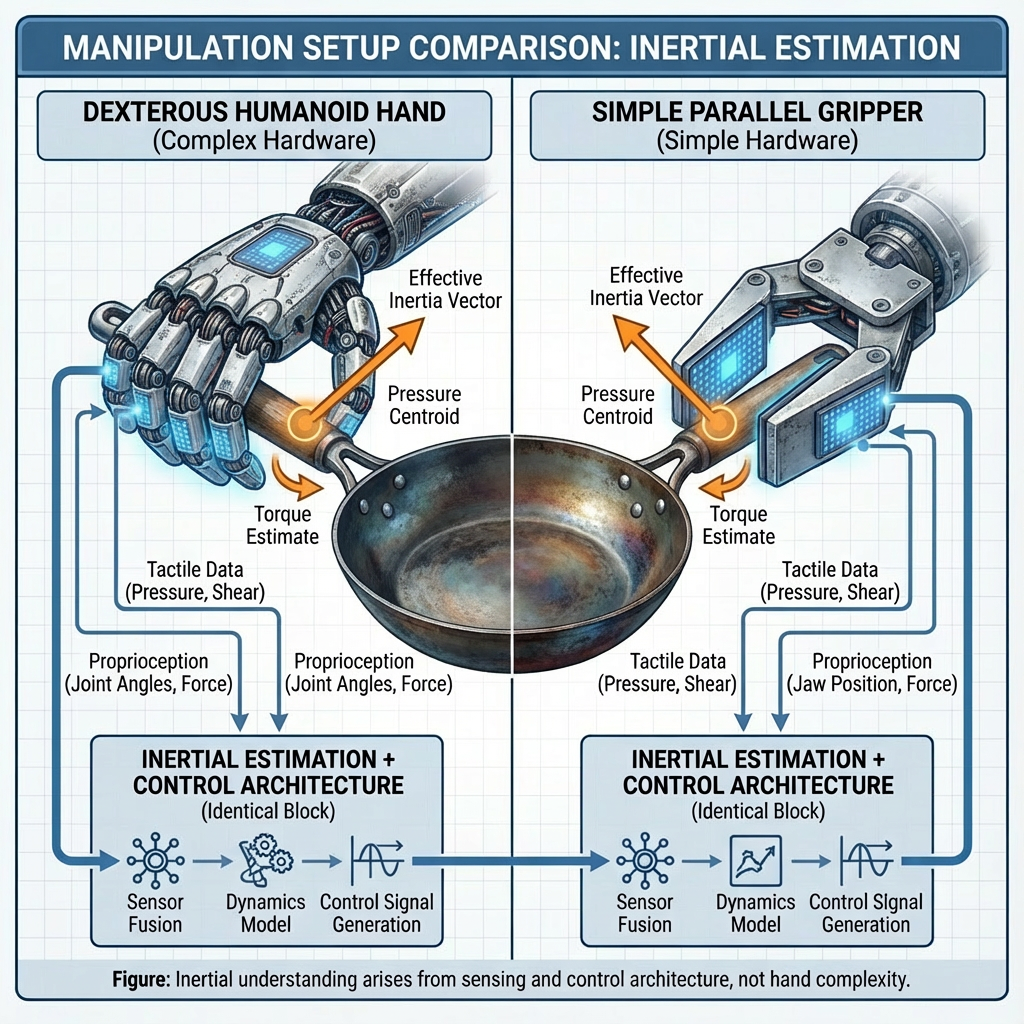

B. Simple Grippers as First-Class End Effectors

Critically, the architecture is hand-agnostic. Highly capable inertial estimation and adaptive control do not require anthropomorphic hands.

Even simple parallel grippers or rectangular gripping surfaces, when equipped with tactile pads beneath a compliant protective layer, can provide sufficient differential information to infer grasp stability and effective inertia. Combined with motor feedback and proprioception, these grippers become extraordinarily capable despite their mechanical simplicity.

Much of the intelligence resides in the sensing, estimation, and control stack rather than in finger geometry.

Figure 8. Inertial estimation is independent of hand complexity.

This dramatically lowers the hardware barrier for practical deployment.

C. Proprioception and Actuation Feedback

Joint encoders, motor current or torque sensing, and ideally a wrist-mounted 6-axis force/torque sensor provide high-bandwidth measurements of applied effort and resulting motion. These signals form the primary channel for inertial inference.

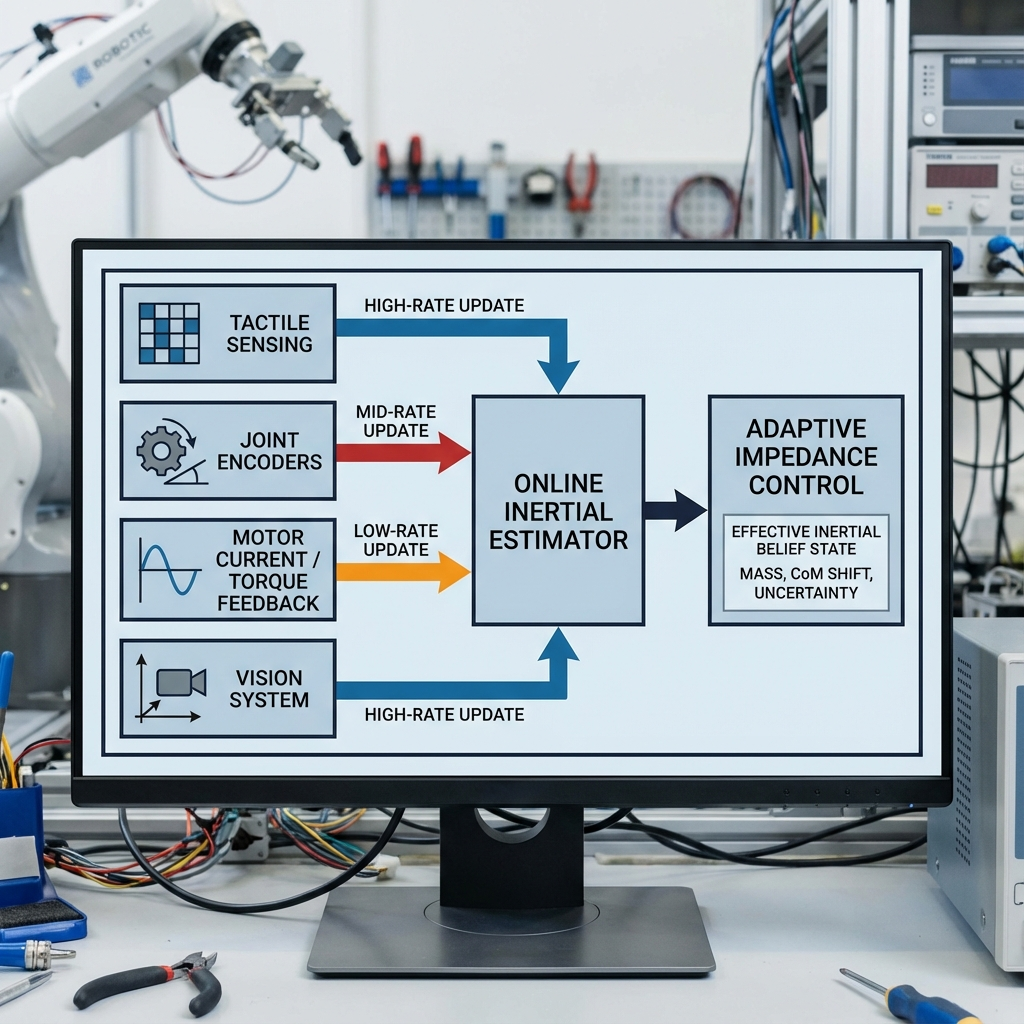

Figure 7. Multi-modal sensor fusion feeding an online inertial estimator.

D. Vision

Vision tracks object pose and robot body pose in workspace coordinates. It operates at lower bandwidth and serves as a supervisory correction layer, ensuring global consistency without constraining reaction speed.

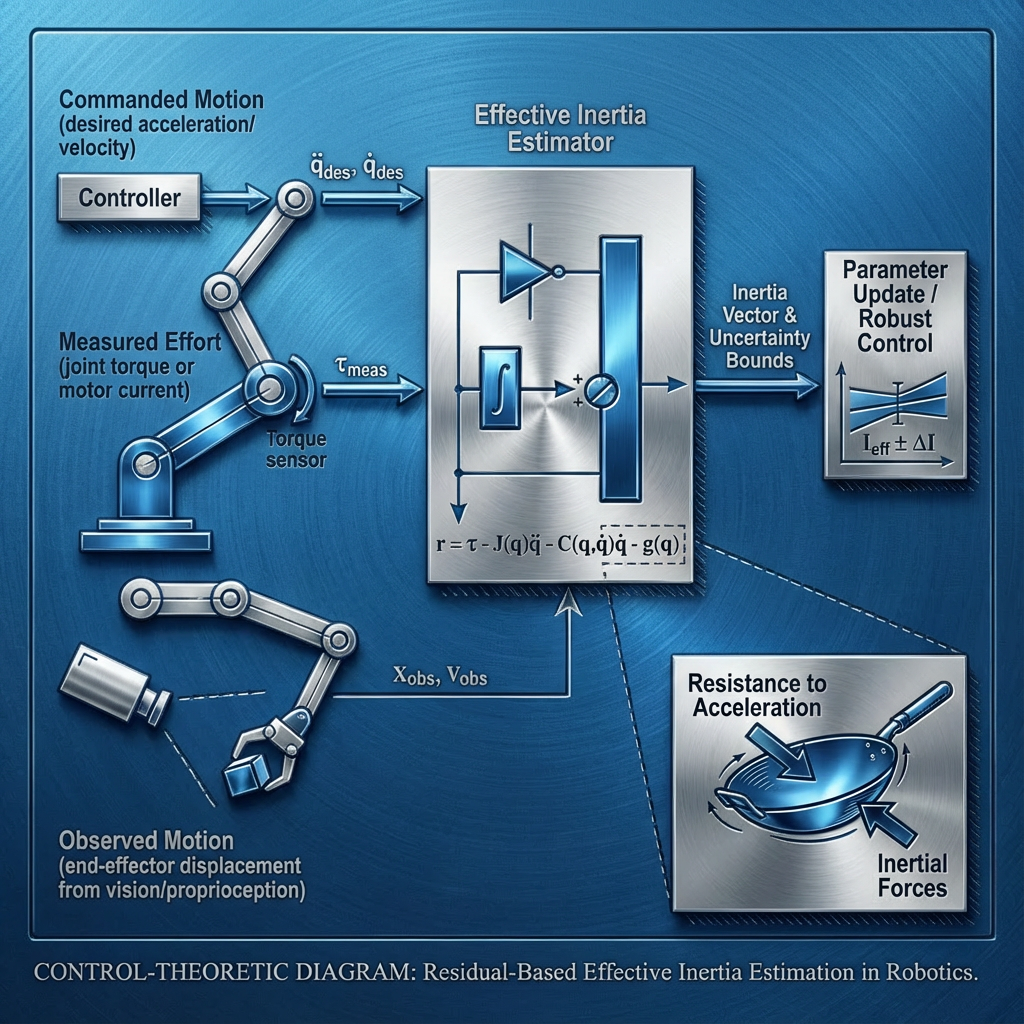

VII. Online Inertial Estimation and Adaptive Control

Using fused sensor data, the system maintains a continuously updated belief over:

Effective mass

Center-of-mass shift

Effective inertia

Disturbance terms (e.g., slosh)

Uncertainty bounds

For non-uniform loads, the system estimates effective inertia, not a full physical simulation.

Figure 9. Residual-based effective inertia estimation and adaptive control.

Control is implemented via impedance or admittance schemes whose gains adapt dynamically to the inferred inertial state.

Learned motion primitives such as stirring, tossing, pouring, and scraping are executed feedforward, with sensory feedback modulating force and timing in real time.

Figure 10. Cooking primitives as abstract manipulation challenges.

VIII. Part II: Latency Collapse and High-Speed Domains

While the baseline system operates effectively within a ~30 ms supervisory loop, the same architecture naturally extends to domains requiring much faster reaction times as sensing technology improves.

If vision latency collapses through high-speed cameras or event-based sensing, the robot’s inertial belief and control loops can update correspondingly faster. This enables tasks such as:

Industrial hazard mitigation

Disaster response

Surgical assistance

Vehicle intervention

High-speed interception

No conceptual redesign is required. The same measurement-grounded, locally densified world model applies. Only sensor latency changes.

IX. Technical Specification (Condensed Implementation Overview)

A minimal implementation requires:

Torque-controllable arm and wrist

Simple gripper or dexterous hand with compliant outer surface

Piezoresistive tactile pads on contact surfaces

Joint encoders and motor torque/current sensing

Wrist-mounted 6-axis force/torque sensor (recommended)

RGB-D or stereo vision system

Software components include:

Online inertial estimator (EKF or recursive least squares)

Grasp-stability gating via tactile signals

Adaptive impedance control

Learned manipulation primitives

Frame-synchronous update loop (~30 ms) with sub-frame reflex clamps

X. Conclusion: Toward Inevitable Utility

If humanoid robots are ever to enter homes and be genuinely useful, they must operate in environments that are messy, dynamic, and poorly specified. Cooking is not an edge case. It is the proving ground.

The system described here does not depend on perfect simulation, complex hands, or fragile assumptions. It depends on sensing, adaptation, and continuous measurement.

Once a robot can feel how heavy something is as it moves it, even with a simple gripper, the rest follows naturally.

In this sense, cooking-capable humanoids are not a question of if, but when. And the path forward is not faster thinking, but better feeling.

KG_LLM_SEED_MAP:

meta:

seed_title: "Measurement-Grounded Manipulation for Cooking-Capable Humanoid Robots"

seed_id: "kgllm_humanoid_cooking_measurement_grounded_v2"

version: "v2.0"

authors:

- "Cameron T."

- "ChatGPT (GPT-5.2)"

date: "2025-09-16"

domain:

- humanoid robotics

- manipulation

- tactile sensing

- inertial estimation

- adaptive control

- human motor control analogy

intent:

- enable cooking-capable humanoid robots

- replace exhaustive global simulation with measurement-grounded local physical modeling

- lower hardware complexity requirements for useful manipulation

- provide a scalable architecture from household to high-speed hazardous domains

core_problem:

statement: >

Modern humanoid robots fail at cooking and other contact-rich household tasks

because they rely on static assumptions about object inertia, vision-dominant

pipelines, and fixed control gains, rather than continuously measuring how

objects respond to applied action.

failure_modes:

- assumes object mass, center of mass, and inertia are static or known

- cannot adapt to sloshing, pouring, or shifting contents

- vision latency dominates reaction time

- lack of tactile awareness prevents grasp-state discrimination

- over-reliance on precomputed simulation rather than real-time measurement

- fixed impedance leads to overshoot, spill, or under-actuation

biological_analogy:

human_motor_control:

description: >

Humans do not continuously react at millisecond timescales during skilled

manipulation. Instead, they execute learned motor primitives in a feedforward

manner, while tactile and proprioceptive feedback modulates force and timing

at slower supervisory timescales.

key_timings_ms:

spinal_reflex: 20-40

cortical_tactile_integration: 40-60

skilled_motor_correction: 80-150

visual_reaction: 150-250

implication: >

A robotic system operating with ~30 ms supervisory updates already exceeds

human cortical correction speed and is sufficient for household manipulation,

including cooking.

timing_and_reaction_model:

baseline_operating_regime:

supervisory_update_ms: 30

limiting_factor: "vision latency"

justification: >

Cooking and household manipulation dynamics evolve on timescales slower

than 30 ms. This regime is conservative, biologically realistic, and already

5–8× faster than human visual reaction.

sub_frame_reflexes:

update_rate_ms: 1-5

mechanisms:

- tactile-triggered impedance increase

- torque clamping

- grasp stabilization

note: >

Reflexive safety responses operate independently of the vision-synchronous loop.

latency_collapse_extension:

description: >

As vision latency decreases via high-speed or event-based sensors, the same

architecture supports proportionally faster inertial updates and control

without conceptual redesign.

enabled_domains:

- industrial hazard mitigation

- disaster response

- surgical assistance

- vehicle intervention

- high-speed interception

system_philosophy:

world_modeling:

approach: >

Hierarchical world modeling with coarse, stable global representation and

locally densified, measurement-driven physical modeling concentrated around

active manipulation and contact.

global_layer:

contents:

- spatial layout

- object identity

- task context

- navigation affordances

resolution: "coarse and stable"

local_physical_layer:

trigger: "on grasp and manipulation"

contents:

- effective mass

- center-of-mass shift

- effective inertia

- disturbance terms

resolution: "high-fidelity, continuously updated"

governing_principle: >

The robot simulates with precision only what it is currently acting upon,

and only after action begins.

sensing_stack:

tactile_layer:

type: "piezoresistive pressure sub-mesh"

placement_options:

- fingertips

- palm surfaces

- flat gripper pads

construction:

outer_layer: "compliant elastomer (rubber or silicone)"

inner_layer: "piezoresistive grid or mat"

signals_extracted:

- pressure centroid drift

- pressure redistribution

- micro-slip onset

- grasp stability index

design_note: >

Absolute force accuracy is unnecessary; differential change detection is sufficient.

proprioception_and_actuation:

sensors:

- joint encoders

- motor current or torque sensing

- optional joint torque sensors

- wrist-mounted 6-axis force/torque sensor (recommended)

role:

- measure applied effort

- infer resistance to acceleration

- detect disturbances

vision_layer:

tracking_targets:

- object pose

- end-effector pose

- robot body pose

role:

- global reference

- supervisory correction

- drift and compliance correction

constraint: >

Vision is the lowest-bandwidth sensor and does not gate reflexive stability.

end_effector_generality:

principle: >

High-capability manipulation is not dependent on anthropomorphic hands.

Intelligence resides in sensing, estimation, and control rather than finger geometry.

supported_end_effectors:

- dexterous humanoid hands

- simple parallel grippers

- flat gripping surfaces with tactile pads

implication: >

Mechanically simple, rugged, and inexpensive grippers can perform complex

manipulation when paired with tactile sensing and inertial estimation.

estimation_targets:

rigid_objects:

parameters:

- mass

- center_of_mass_offset

- inertia_tensor

non_uniform_objects:

strategy: >

Estimate effective inertia and disturbance rather than full physical models.

disturbances:

- slosh dynamics

- particle flow

- friction variability

rationale: >

Control robustness emerges from measurement and adaptation, not exact simulation.

estimator_logic:

update_conditions:

- grasp stability confirmed via tactile sensing

- no excessive slip detected

- known excitation or manipulation motion

gating_behavior:

description: >

Inertial estimates are frozen or down-weighted when grasp instability is detected,

preventing slip from being misinterpreted as inertia change.

control_layer:

method:

- impedance control

- admittance control

adaptation:

- gains scaled by estimated inertia

- acceleration limits scaled by uncertainty

primitives:

- stir

- toss

- pour

- scrape

- fold

safety_mechanisms:

- torque saturation

- motion envelope constraints

- rapid abort on instability

application_domains:

household_baseline:

tasks:

- cooking

- cleaning

- tool use

- general manipulation

characteristics:

- 30 ms supervisory loop

- sub-frame reflex safety

- high robustness

extended_high_speed:

tasks:

- hazardous environment operation

- industrial intervention

- surgical assistance

- vehicle control

- interception

enabling_factor: "sensor latency collapse"

key_insights:

- >

Cooking is not an edge case but the proving ground for general-purpose

adaptive manipulation.

- >

Effective intelligence in manipulation arises from sensing and measurement,

not exhaustive prediction.

- >

Once a robot can feel how heavy something is as it moves it, the rest follows naturally.

inevitability_statement:

summary: >

If humanoid robots are ever to be useful in real homes and real environments,

measurement-grounded, inertial-aware manipulation is not optional. It is inevitable.

paper_structure_hint:

recommended_sections:

- Introduction: Why robots still cannot cook

- Static assumptions vs dynamic reality

- Human motor control and timing

- Robotic reaction time and vision limits

- Measurement-grounded local world modeling

- Multi-modal sensing and end-effector generality

- Online inertial estimation and adaptive control

- Latency collapse and high-speed extensions

- Technical specification

- Conclusion: Inevitability of adaptive humanoids